While one might think that they are far enough from land to be safe from anthropogenic (man-made) threats, this is unfortunately not the case. Pelagic habitats are frequented by numerous fisheries targeting species of high commercial value such as tuna and swordfish, whose habitats often overlap with those of sea turtles.

Darwin’s tag is fitted with a pressure sensor that collects data on its diving behaviour, as well as its location. Its behaviour is consistent with what we’ve observed in other young loggerheads: Darwin most often stays within the first 5 metres under the ocean, but sometimes makes deeper dives. We hope that, when we analyse these data in more detail, we will learn more about how these dives may be linked to environmental factors or other loggerhead turtle behaviours.

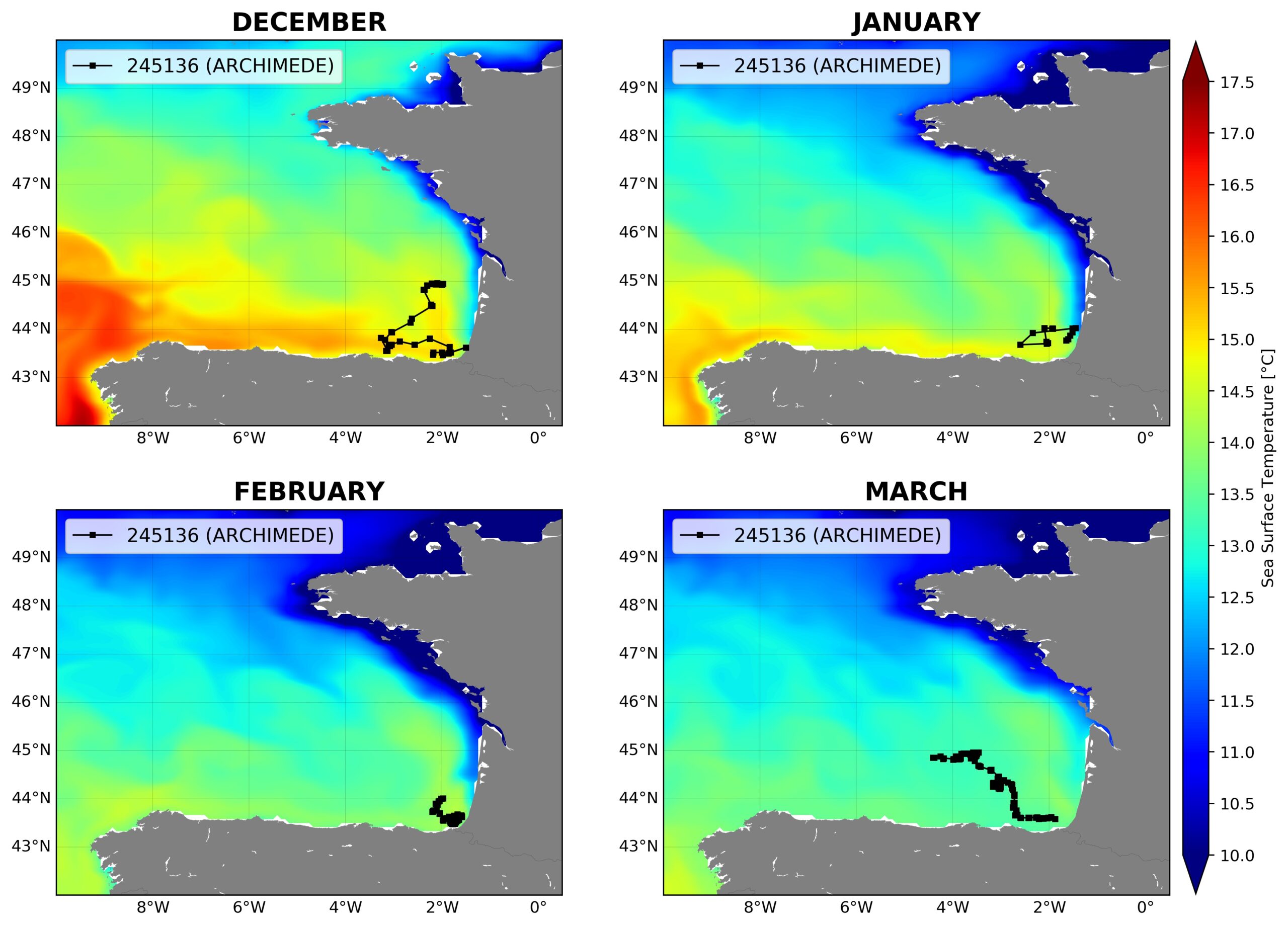

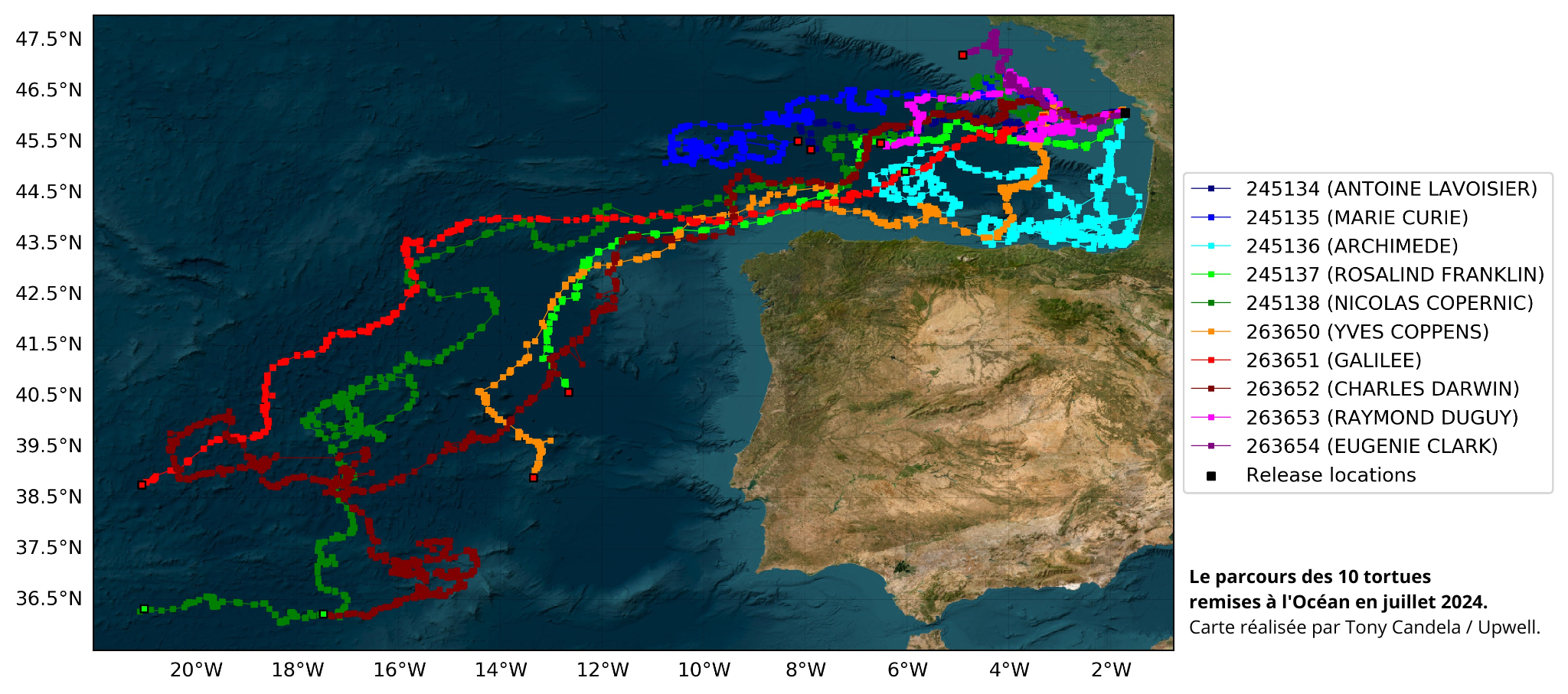

While the Darwin, Archimedes and Nicolas Copernicus beacons continue to transmit data, another group of young loggerhead turtles rehabilitated at the Aquarium La Rochelle are preparing to return to their natural environment, also with beacons. By increasing the sample size, we can generate more robust statistics and develop more solid hypotheses. We can then integrate environmental datasets to examine correlations between the turtles’ horizontal and vertical movements and environmental factors such as sea surface temperature, productivity or chlorophyll concentrations, current speed, sea surface height or bathymetry. The monitoring data and analyses give us a rare insight into the time that juvenile loggerhead turtles spend foraging and growing (up to 15 years) at sea, often referred to as their “lost years”, so little is known about this period of their lives. We use this information to calibrate various models that can help us predict sea turtle habitat use or even population trends – models that aim to support effective and targeted conservation efforts.